Starting a concept map with a blank canvas may be not only a challenge, but is found to be sometimes intimidating (Kinchin 2001). This is particularly the case when the Cmap covers a topic with which we are not very familiar, and we don't really know "where to begin". This is often the case with students at the beginning of a unit, when they are just starting to understand the topic.

We have found that different techniques may help the students express their understanding and build Cmaps. One such technique is through games in which students joint concepts to form propositions, and which has shown to result in more more complex Cmaps, from both students and teachers, than when starting from a blank canvas. Games help users find out that they are able to construct complex maps.

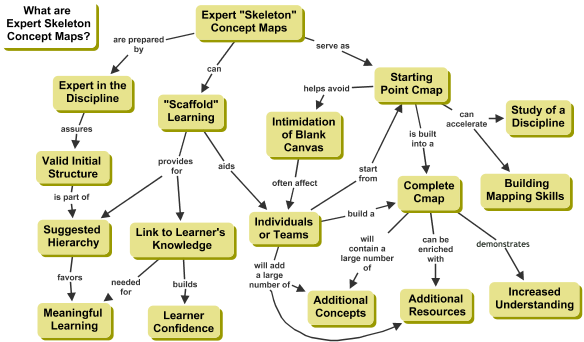

Another technique that can be used consists of providing the learner, as a starting point, a simple map composed of the key concepts for the topic and which has been constructed by subject matter expert. We call this map an Expert Skeleton Concept Map (ESCM). Figure 1 explains the ideas behind the use of Expert Skeleton Concept Maps.

Figure 1. Expert Skeleton Concept Maps as an aid to scaffold learning.

The idea of using an Expert Skeleton Concept Maps (ESCM) is to provide a learner with a small concept map for any given knowledge domain that is prepared by an expert in that domain. Normally this map would have 6-10 concepts with proper linking words and a good hierarchy. The learner is asked to continue the construction of the concept map, resulting in a map with around three times the number of concepts in the original ESCM.

With the ESCM we pursue several goals:

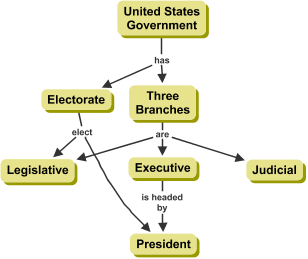

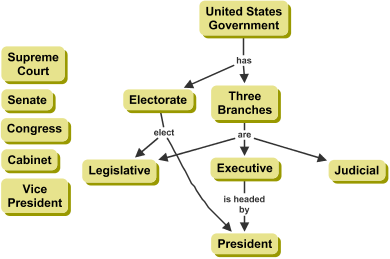

Figure 2 shows an example of an expert skeleton concept map for US government. The ESCM might also include a list of other relevant concepts that the learner can add to ESCM. We call this list of concepts for inclusion a Parking Lot, and concepts can be moved from here into the appropriate places in the ESCM, as shown in Figure 3. Using a parking lot along with an ESCM provides additional scaffolding for the learner and might be most appropriate for a beginner in concept mapping or when introducing a new topic of study.

Figure 2. An example of an Expert Skeleton Concept Map.

Figure 3. Sample Expert Skeleton Concept Map with concepts on the Parking Lot on the left, to be added by the learner to the concept map.

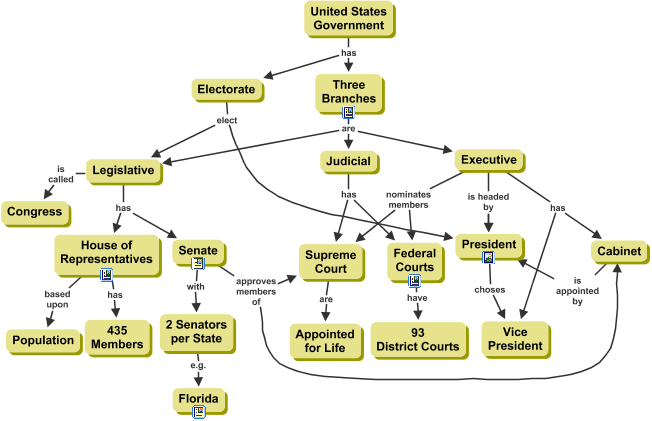

Using CmapTools, a learner can proceed to build a more complete concept map by drawing on personal knowledge, using information in texts, documents, and syllabus, the Web, or using the Search Tool in CmapTools and identifying other relevant concepts and propositions that might be incorporated. The latter tasks require a learner to assess the importance and relevance of new concepts and propositions and to determine how they can be meaningfully integrated into the ESCM. The latter tasks involve the high levels of cognitive thinking as proposed by Bloom (1956), namely evaluating the pertinence and importance of concepts and propositions to be included and synthesis of this information into the existing knowledge structure.

We have proposed a New Model of Education based on a concept map-based learning environment where the learner -- together with his/her colleagues if working collaboratively -- continues constructing the concept map built at the beginning of the unit as he/she/they advance in their learning, demonstrating the increased understanding. The ESCM is an excellent starting point, whereby the students add a significant number of concepts and linked resources through their work on the unit.

Figure 4 shows how the ESCM in Figure 2 might be elaborated with additional concepts and propositions, and also icons to access resources that have been linked by the students.

Figure 4. One example of how the ESCM in Figure 2 might be elaborated, by an individual or by a collaborating team, including icons for accessing linked resources. The map is not finished and can be further developed.

The process of building upon and elaborating ESCMs can lead to highly meaningful learning, since the builder is actively engaged in the process, especially as she/he seeks the best linking words to relate concepts and the best organization of the concept map. However, getting started on the construction of the Cmap may be at times intimidating, and starting an Expert Skeleton Concept Map is a way to help the student start building the map by taking advantage of the scaffold prepared by a domain expert.

Ausubel, D. P. (1963). The Psychology of Meaningful Verbal Learning. New York, Grune and Stratton.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; the Classification of Educational Goals. New York, Longmans Green.

Bransford, J., A. L. Brown, et al., Eds. (1999). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. Washington, D.C., National Academy Press.

Kinchin, I. (2001). If concept mapping is so helpful to learning biology, why aren't we all doing it? International Journal of Science Education, 23(12), 1257-1269.

Novak, J. D. (2002). Meaningful Learning: the Essential Factor for Conceptual Change in Limited or Inappropriate Propositional Hierarchies (LIPHs) Leading to Empowerment of Learners. Science Education 86(4): 548-571.

Last update: May 10, 2010