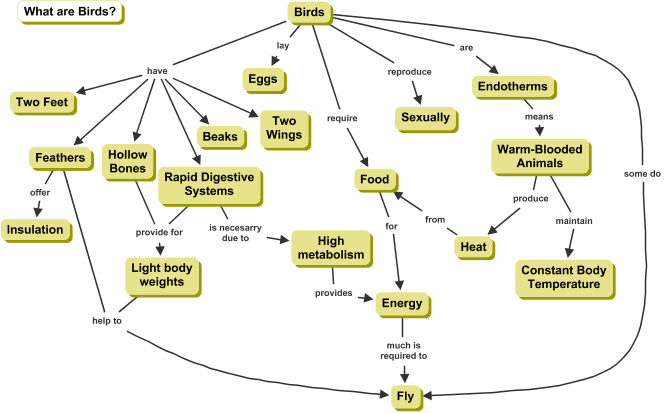

Concept maps are graphical tools for organizing and representing knowledge. They have two key components, "concepts" and "linking words" (also referred to as "linking phrases"). The linking words are used to join two or more concepts, thereby forming propositions. In the concept map in figure 1, "Birds", "Rapid Digestive Systems" and "High metabolilsm" are concepts, "have" and "is necessary due to" are linking words, and together they form the two propositions "Birds have Rapid Digestive Systems" and "Rapid Digestive Systems is necessary due to High Metabolism", among others. Therefore, understanding what concepts are is a basic step in understanding concept maps and how to construct and use them. In this document we attempt to describe what a "concept" is from a concept mapping perspective.

Figure 1. Concept map about Birds

Novak (1984), based on Ausubel's (1968; 2000) and Toulmin's (1972) work, defines "concept" as a perceived regularity or pattern in events or objects, or records of events or objects, designated by a label.

Words are one way to describe and name concepts, they are used as labels for concepts. "Dog", "boat" and "tree" are example of words that are labels for objects. When a concept is named, the word is a label that maps onto our conceptual structure. With object-type concepts, such as "dog", the word maps into a category that describes this particular type of animal, with all its possible variations in terms of dog size, color, etc. The regularities in the object determine its category. Flavel, Miller & Miller (2002) roughly define a concept as a mental grouping of different entities into a single category on the basis of some underlying similarity – some way in which all the entities are alike, some common core that makes them all, in some sense, the same thing. The label for most concepts is a single word, although sometimes we use symbols such as + or %, and sometimes more than one word is used.

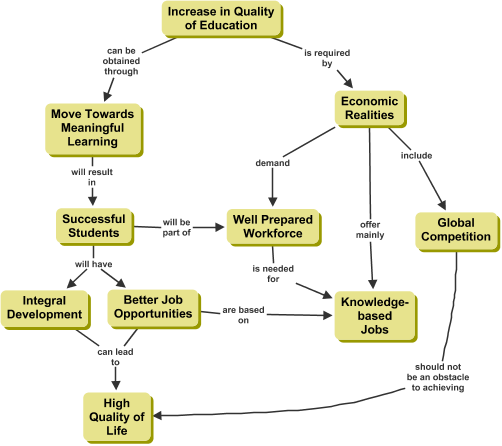

The universe consists of objects and events. Both objects and events are needed to represent knowledge about the universe and its contents. We usually think of events as happenings such as a "party" or a "meeting". Happenings, however, include changes in status like occurrences or improvements. For example, "increase in quality of education" is an event-type concept, and so are "adoption of constructivism" and "growth of plants". An examination of a large number of concept maps has shown that the majority deal mainly with objects, not with events (Safayeni et al., 2005). Moreover, experiments and our experience show that using event-type concepts lead to concept maps that are more explanatory in nature, while object-type concepts lead to more descriptive, often classificatory, concept maps. figure 2 shows a concept map where the concepts "Increase in Quality of Education" and "Move Towards Meaningful Learning" are events.

Figure 2. Concept map on Increase in Quality of Education

The question sometimes arises as to the origin of our first concepts. These are acquired by children between birth and three years of age, when they recognize regularities in the world around them and begin to identify language labels or symbols for these regularities (Macnamara, 1982). Piaget showed that the construction of meanings occurs even before the language acquisition (Piaget & Inhelder, 1976).This early learning of concepts is primarily a discovery learning process, where the individual discerns patterns or regularities in events or objects and recognizes these as the same regularities labeled by older persons with words or symbols. This is a phenomenal ability that is part of the evolutionary heritage of all normal human beings. After age 3, new concept and propositional learning is mediated heavily by language, and takes place primarily by a reception learning process where new meanings are obtained by asking questions and getting clarification of relationships between old concepts and propositions and new concepts and propositions. This acquisition is mediated in a very important way when concrete experiences or props are available; hence the importance of “hands-on” activity for science learning with young children, but this is also true with learners of any age and in any subject matter domain.

It is impossible to characterize any concept without its relation to other concepts. If one considers object-type concepts, the categories they evoke have common properties (e.g. dogs are pets, mammals, within certain size, etc.) that define the category, and therefore the concept is defined by its relations to these other concepts. So a concept does not exist by itself, it is part of a conceptual system in which elements are related to each other.

More abstract concepts however cannot be described as having a cognitive representation as a category. For example, what classes of entities are grouped together to define "rate of change" as a category? Thus concepts may not be categories. In fact, most people may have difficulty giving an example for abstract concepts such as "intelligence", "motivation", "personality", and "social dilemma", just to name a few. People also have a hard time describing patterns or regularities in abstract terms such as "evolution", or "constructivism".

Ausubel, D. P. (1968). Educational Psychology: A Cognitive View. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Ausubel, D. P. (2000). The Acquisition and Retention of Knowledge: a Cognitive View. Dordrect; Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Novak, J. D., & Gowin, D. B. (1984). Learning How to Learn. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Piaget, J. & Inhelder, B. (1976). Da Lógica da Criança à Lógica do Adolescente. São Paulo: Pioneira.

Safayeni, F., Derbentseva, N., & Cañas, A. J. (2005). A Theoretical Note on Concept Maps and the Need for Cyclic Concept Maps. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 42(7), 741-766.

Toulmin, S. (1972). Human Understanding. Volume 1: The Collective Use and Evolution of Concepts. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Last update: June 21, 2009